Black History Month - Robert William Stewart

by Pebbla Wallace, LACHS Board Member

Robert William Stewart (1850-1931) – the forgotten story of first African American police officer in California serving at the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD)

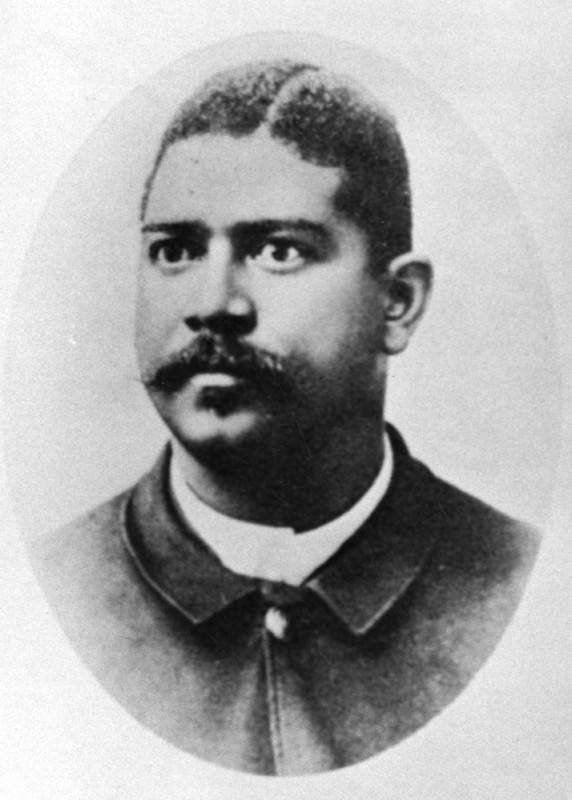

Robert Stewart

Photo Credit: Security Pacific National Bank Collection / Los Angeles Public Library

The story of Robert Stewart may have been forever lost if not for the diligent research of historian Mike Davison who first came across Stewart’s name in 2015. While researching the history of one of our earlier City Halls located near 2nd and Spring Street, which later became the headquarters of the LAPD for approximately 11 years, Davison stated that he came across his name purely by accident in an 1889 record that showed Stewart as becoming a LAPD Officer - but no one knew what had happened to him after that. Davison and some fellow researchers (including retired LAPD Lt. Rita Knecht) were able to obtain information through official documents, various newspaper articles, and genealogy records.

Stewart’s Beginnings. Stewart’s early life was difficult to piece together because of very little documentation, and the fact that most early census records before 1870 rarely list slaves as people, but as property. But just like most African Americans during this period, Stewart’s story begins when he was born into slavery (by Stewart’s own account). He was born in Garrard County Kentucky on March 1, 1850, to Faulkner Stewart and Ellen Doty. He later gained his freedom shortly after the Civil War. The 1870 Census records indicate Robert was able to both read and write, which was rare for a former slave at the time. Sometime around 1871 he met and married Louise Coffey (also a former slave). Robert and Louise stayed in Kentucky where Robert worked as a laborer. In 1877 they had a son named William Malcom Edgar Stewart – their only child. In 1880, Robert and Louise lived in the household of a widowed white farmer in Stanford where they both worked as servants. Sometime later, Robert and his family moved to Jeffersonville, Indiana where he worked for the Ohio Falls Car Company. According to the California Voter records, they lived in Los Angeles as early as 1884 – where Robert worked mostly as a janitor and a laborer, and then in 1887-1889 for a freight-hauling company.

Stewart was also a member of the Colored Republican Club which was an influential political group in Los Angeles at the time, and which was persuasive in getting many politicians elected to office.

Stewart’s Time at the LAPD. On March 31, 1889, Robert Stewart and Joseph Green were appointed as Los Angeles LAPD Officers – the first Black officers in California and the City of Los Angeles. (Note: Green’s career was short-lived when a little over a year he was among nine officers that were laid off).

Originally, Stewart and Green had been placed in minor positions at the LAPD. There were major complaints by Los Angeles’ Black community, and on April 2, 1889, a Letter to the Editor was published in the Los Angeles Times that stated, “I ask permission to make the inquiry through your paper why only two of the applications from colored men to be placed on the police force were considered, and why the city authorities are dilatory in placing the two Colored men appointed on the force to active duty, and why they should be relegated to janitor duty in the city buildings?”

Shortly after this letter was published, Stewart was assigned to traffic duty on First and Spring Street (the busiest intersection at the time) directing traffic, and then later as foot-patrolman around the same area. Originally there were both negative and positive reactions to seeing a Black person wearing the blue uniform. Stewart’s 6’4, 240-pound frame (considered extremely large at the time), gave way to some offensive headlines, referring to Stewart as “the big colored policeman”, or “the colored giant in blue”. Some insulting headlines blended into complete racist remarks including a July 22, 1897, LA Times article depiction of Stewart capturing a team of runaway mules, stating, “the burly policeman sunk his Ethiopian heels into the cobblestones”. In other articles there were references to Stewart as the “dusky copper” “or the “thickness of his African skull”. But as time went on, there were many articles that praised Stewart’s bravery. For example, in a November 30, 1895, article in the Los Angeles Times it stated, “Officer Stewart is the only colored man on the force, but he has a record for bravery and good conduct that has never been questioned.”

Stewart became a well-respected officer in the community by many, according to hundreds of articles in the Los Angeles Times and Herald. Stewart was mentioned in the local papers on a regular basis, and his police career was followed by the news media both on the streets of Los Angeles and in the courtroom where he testified regularly.

His respect went beyond his career as an officer when he also endorsed medical devices in the local papers that assisted in relieving various ailments. For example, a July 29, 1896 ad in the LA Times stated “Mr. R.W. Stewart, a well-known police officer of this city tells of his cure by Dr. Sanden’s Electric Belt”.

Nomination for Constable. Around 1892 much of Los Angeles County was divided into smaller districts called townships which were policed by elected peace officers called constables. The Los Angeles township at the time had two white constables. Prior to the re-election period, the Los Angeles County Republican Party was persuaded by various Black leaders, the founder and editor of the oldest Black newspaper in the west John Neimore, and the Los Angeles’ Negro Republican Club to nominate Stewart to one of the constable positions. Stewart became the County’s first major-party Black candidate to be nominated for an elected office.

Stewart resigned from his position at the LAPD after his nomination to concentrate on his election. Stewart spoke at various Republican rallies throughout the city in an attempt to obtain votes. But in the end, he lost and came in third. There were many complaints by the Los Angeles Black community. In a November 27, 1892, Letter to the Editor in the Los Angeles Herald, it stated, "the shameful manner in which the Republicans treated our friend, Mr. R. W. Stewart, candidate for constable on the Republican ticket. The Republicans are loud in promises to the colored people, but when it comes to fulfillment we have, in the defeat of Mr. Stewart, an evidence of their insincerity." Stewart was reappointed back as an officer in January 1893.

The Event that Changed Stewart’s Life. Stewart served as an LAPD Officer for almost 11 years, when his career ended with a major injustice that has long been forgotten by most Angelenos for more than 120 years.

On May 10, 1900, Stewart was arrested and charged with the rape of a 15-year-old white girl name Grace Cunningham. Cunningham claimed that sometime on May 9 around midnight, she met Stewart. When Stewart was escorting her home, he took her to a secluded area and raped her. Stewart declared his innocence. He did admit meeting her, but denied touching her or even walking her home.

The following day Stewart was arraigned and bail was set at $1,500 –which his friends helped obtain. Most of his friends and much of the Black community expressed disbelief regarding the charges. Even the May 12th issue of the Los Angeles Times noted “Stewart has long been one of the foremost men of his race in this city". Stewart was represented by two well-respected attorneys Le Compte Davis and Judson Rush, who were both former L.A. County Deputy District Attorneys. At Stewart's preliminary hearing, Black Angelenos packed the courtroom.

During the preliminary hearings cross-examination on May 21, Grace Cunningham changed much of her original testimony from her original statement on May 10. One of the major changes is that she now claimed that Stewart had offered her money for sex, and instead of going straight home as she originally indicated, she now claimed she spent the next hour and a half afterward talking to a tamale vendor. There were other inconsistencies in her statement during the hearing, and her character was often called into question. Also, during this preliminary hearing, Stewart’s bail was raised to $3,000 – double what was set originally. Unable to afford the additional bail, he was sent to jail to await his trial.

Stewart Dismissal from the LAPD. Sometime after the charges against Stewart, Police Chief Charles Elton suspended Stewart and forced him to surrender his badge and equipment. He also recommended that the police commission fire him. On June 5, 1900, with a vote of 3-2 in favor, the commissioners’ officially fired Stewart from the LAPD.

Trial No. 1. After a major delay, Stewart’s trial began on October 22, 1900. According to the LA Times, most of the courtroom's seats were taken up by many in the Black community, and it was standing room only. The jury of 12 white men was chosen and carefully questioned for their impartiality, racial biases, and other issues.

Grace Cunningham was the first witness. She duplicated approximately the same testimony from the preliminary hearing. She was then cross-examined by the defense. [Note: Although the local papers reported detailed information regarding Cunningham’s testimony and her rape by Stewart, they did not report or provide any information regarding any of her cross-examination by the defense.]

Stewart's defense called respected character witnesses such as a judge and Stewart’s wife. Stewart testified in his defense and the LA Times indicated that Stewart "made a favorable impression." According to the LAPD Museum, during his testimony “Stewart claimed that at the time of the alleged assault, he was patrolling another part of his beat, which covered the blocks between Fifth and Tenth Streets and Broadway and Hill Street. He admitted meeting Cunningham and scolding her for being out so late, but he had not walked with her or had any physical contact with her”. In the defense closing argument, Stewart's lawyers claimed that Stewart couldn’t have assaulted Cunningham based on the timeline of events as attested to by the witnesses.

The jury deliberated for 1½ days and reported to the judge that they could not agree and were hung. It was later revealed that the initial vote of the jury had been 7 to 5 to acquit Stewart. The judge declared the jury hung, but the District Attorney decided to retry Stewart. The judge reduced Stewart’s bail from $3,500 to $1,000. Stewart’s friends were able to come up with the bail and Stewart was released from jail.

Trial No. 2. The second trial began on December 28, 1900, with Grace Cunningham and her mother testifying. According to various papers, they repeated the same testimony from the first trial. But according to the Los Angeles Evening Express, Stewart's lawyers were able to poke holes in Grace's testimony, "riddling her story until it looked but a skeleton of its former self." The other papers rarely reported information regarding the second trial. Closing arguments began on December 31 and then were submitted to the jury that afternoon. The jury came to a verdict in less than 40 minutes proclaiming Robert William Stewart “not guilty”. Stewart’s innocence was only briefly reported in the papers.

Post-Trial. Stewart served honorably for almost 11 years as an LAPD Officer and was well-respected among both Black and White Angelenos. But even though Stewart was cleared of all charges the LAPD denied his reinstatement into the department.

The false accusation against Stewart ruined his reputation and the profession that he loved so much. It also stripped him of a police pension which he so rightly earned and deserved. After the trial, Stewart worked mostly as a janitor in Los Angeles until his death on July 27, 1931, when he died of prostate cancer. The headlines in the major black newspaper the California Eagle stated “Pioneer was first Negro Policeman in this city”. “Robert W. Stewart, a resident of this city since 1885 is well known and a great fraternal worker and useful citizen, passed to his reward at his home. Known far and wide for his staunch and dependable character, Stewart was honored for his integrity and public-spirited citizenship.” The other local papers barely mentioned Stewart’s death.

Stewart Reinstated as LAPD Officer – Over 120 years too late? On February 2021, the Los Angeles Police Commission voted unanimously to reinstate Robert Stewart, recognizing the injustice of his termination and naming a room after him at Police Headquarters. “This was one way we could show that Black folks in this country have made a difference,” said William Briggs, the police commissioner who brought the motion for reinstatement.

Unfortunately, there is no one left of the Stewart family to see this LAPD reinstatement. The Stewart family is now dead and buried – his wife died in 1933 and his only child William died in 1936 (his son had no children). So how do we rectify this wrong? By continuously telling his story.

Davison states about Stewart’s life, “He suffered what happened to him in silence…he’s a pioneer. He should be remembered like Biddy Mason or any of the other early African American pioneers in Los Angeles.”