The Double Vision of George Rodriguez

by Richard Ross, LACHS Board Member and Newsletter Editor

This article was published in the Spring 2001 issue of the LACHS newsletter. All photos courtesy of George Rodriguez.

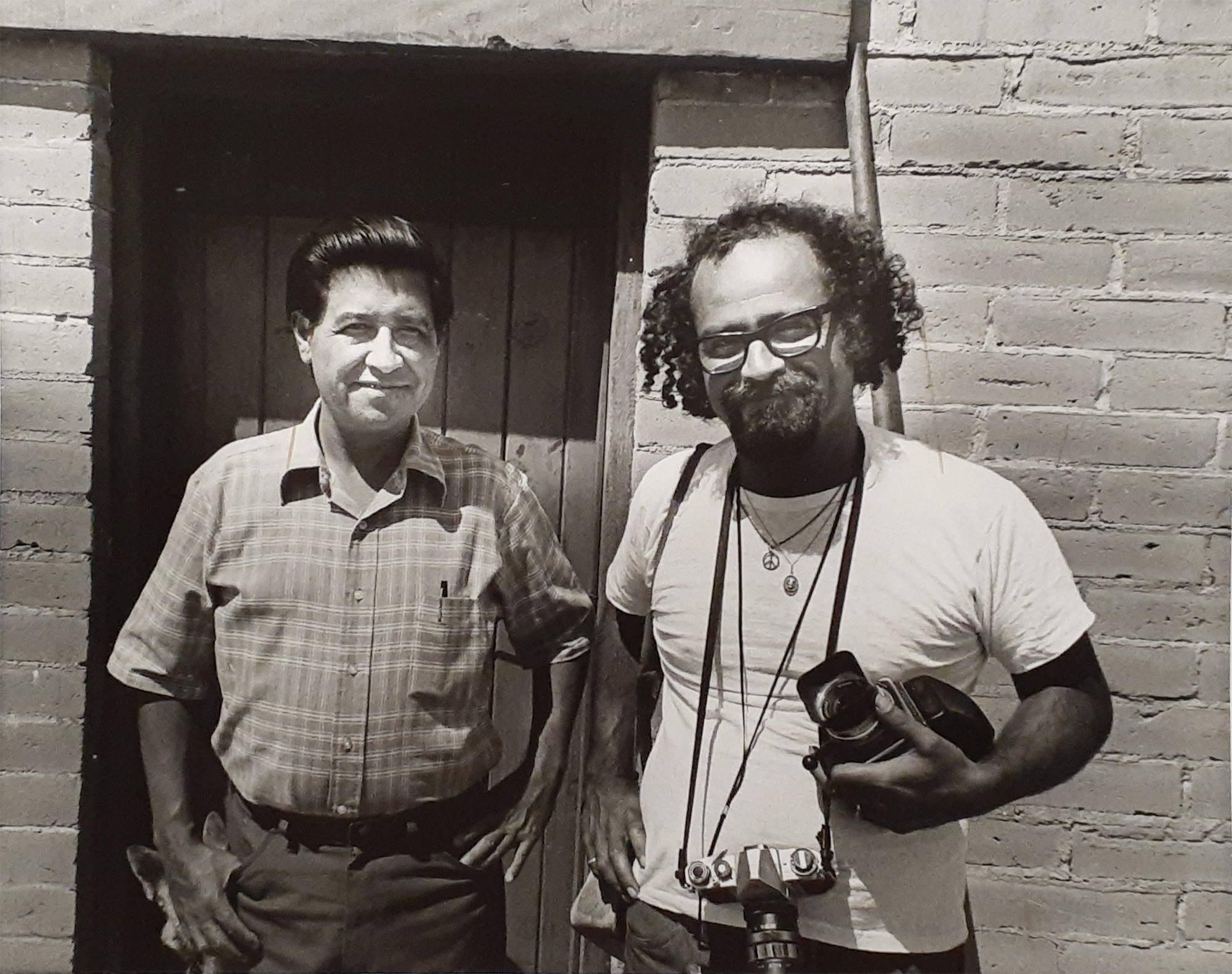

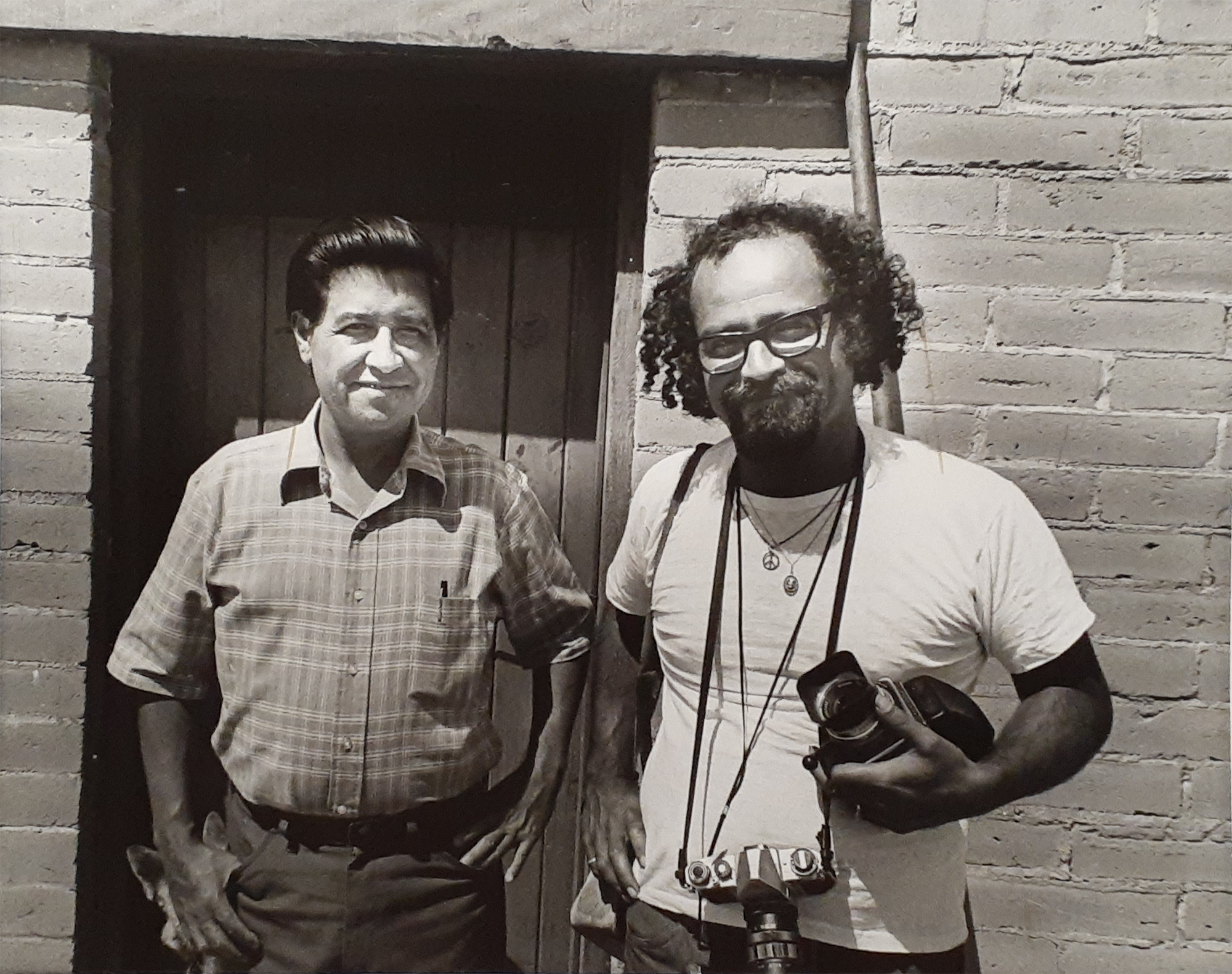

George Rodriguez with Cesar Chavez, Delano, CA 1969

George Rodriguez has been a professional photographer since the 1960s. During those five decades, he has photographed some of the most famous movie and television celebrities of our time as well as rock stars and sports heroes. But Rodriguez has also documented the culture and political events of the Mexican-American community in Los Angeles. The result is a compelling body of work that reveals two very distinct views of Los Angeles: life on the red carpet and life on the streets. His work is a visual record of some of the seminal episodes in the city’s history: the Sunset Strip riots of the 60s, the Chicano movement of the early 70s, the United Farm Workers movement and the 1992 Los Angeles riots.

Earlier this year, we spoke (via Zoom) to George about his career and the social events he witnessed and documented in his work.

George Rodriguez was born in 1937. His parents met in Texas but they moved to Los Angeles not long after they were married. His father opened up a shoe repair shop near Skid Row in downtown Los Angeles and the family settled in South Los Angeles. George attended Fremont High School, where he first discovered photography... almost by accident.

GEORGE RODRIGUEZ: There was a guy, a friend of mine, and I needed an elective. And so I told him and he said, “Take photography. It’s easy.” So that’s what I did.

George enjoyed photography but, at first, it wasn’t really a passion for him but simply a way to make money. He soon got a job at a local film lab.

GR: I started in a photo lab when I was 15 and I was still in high school. I worked there after school. And so then when I graduated, I went to work full-time.

One day in 1957, George had a chance encounter with legendary celebrity photographer Sid Avery.

GR: I took a friend of mine, who was looking for a job, to Hollywood. And while he went to apply for this job, I parked in front of Sid Avery’s studio on Cahuenga. And I saw this guy inside the door way, setting up to take some photos, so I walked in and there was Sid Avery. And so I chatted with him and then he told me he was starting a color lab upstairs. So I went up and applied and I started working there on Cahuenga near Sunset.

Working for Sid Avery opened up a whole new world for George.

GR: When I went to work for Sid Avery, I worked in the photo lab, but he also had me assist him. So I would go with him on shoots. I remember I helped him shoot Lucille Ball at her home.

This was George’s first encounter with the world of celebrity photography. It led to a brief job as a ship- board photographer for a cruise ship. Not long after returning to Los Angeles, George got a job at the film lab for Columbia Pictures.

GR: Columbia Studios could not afford to run their own lab. So they closed it and this guy wanted to re-open it, and he asked me if I wanted to come and set up a photo lab and I was pretty naive, but I said, yeah. So, I was like 20, 21 and running a photo lab at Columbia studios on the Columbia lot.

While working at Columbia, George got his first chance to photograph celebrities on his own.

GR: The way I got started shooting red carpet stuff, is that the real photographers would shoot the stars in the studios, but they would also get press credentials in the mail. And it would be beneath them to go show up on a red carpet somewhere. So they would give me their press credentials. I would go and I just loved it. I worked on speculation, I would shoot stuff and then put a little package together and send it to the magazines. They rarely bought anything, but when they did it, it was a huge deal for me, you know, so that’s how I began.

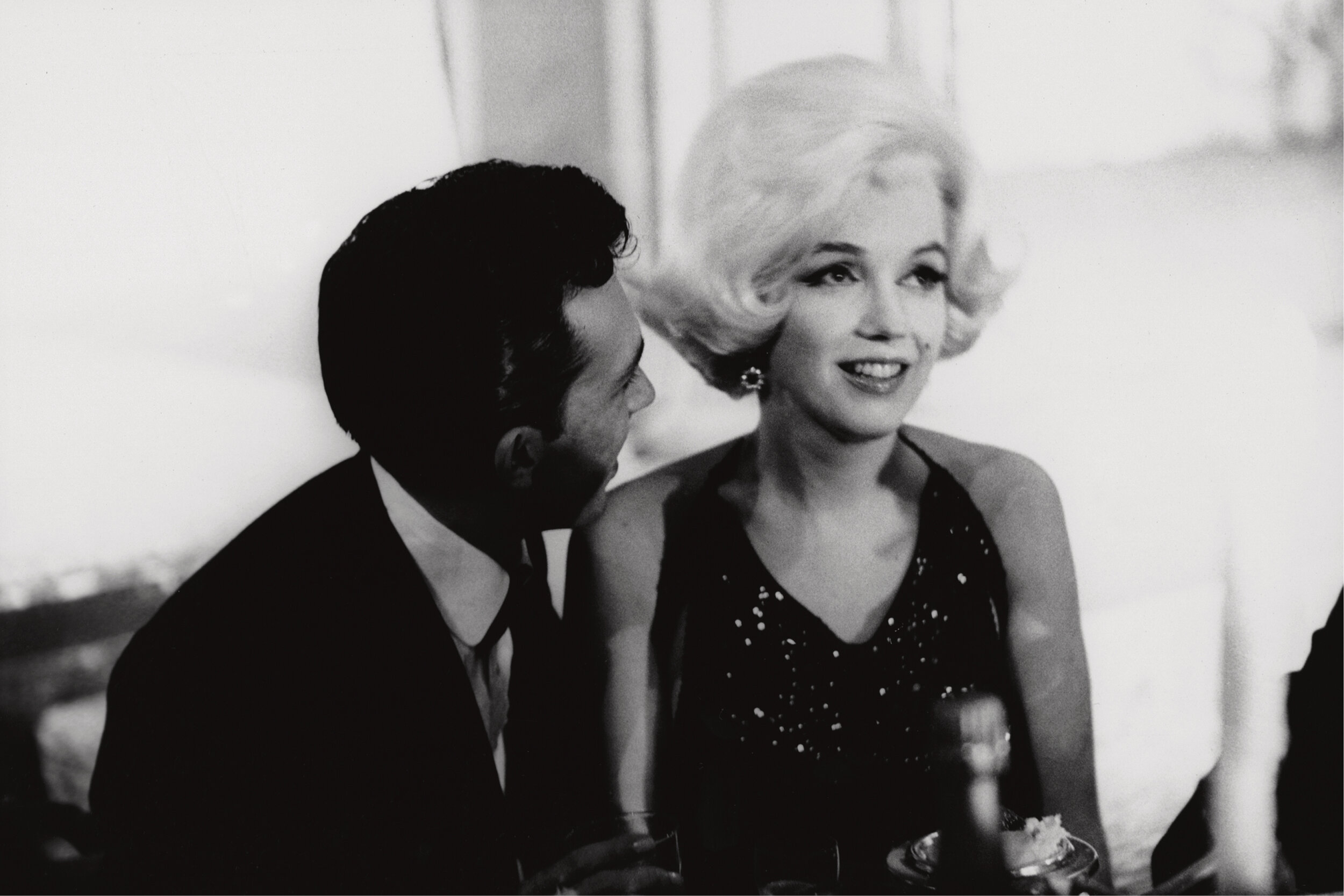

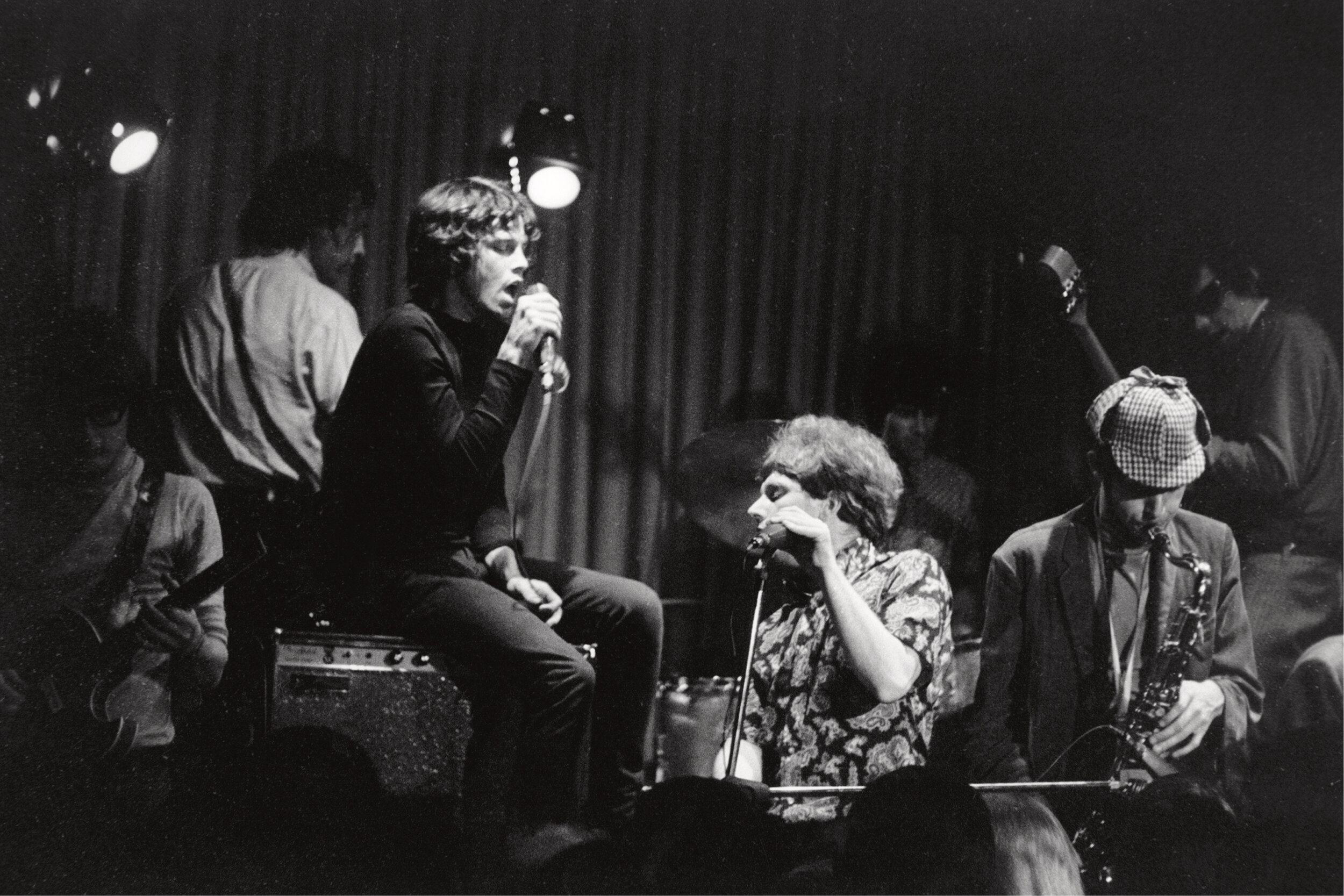

George would spend the 1960s documenting some of the most famous movie stars and musicians of the era, including Lucille Ball, Frank Sinatra, Marilyn Monroe, Cary Grant, and Natalie Wood, as well as rock icons such as Elvis Presley, Jimi Hendrix, Johnny Rivers and Jim Morrison.

GR: I just loved it. You know, you’re kind of on the inside, but you’re on the outside, you know, I would be there.

Rodriguez was one of the first photographers to capture the nascent genius in a very young Michael Jackson.

GR: I felt that this kid, Michael Jackson would be a superstar. And then from like, from that moment on, he was a big star.

But far from the glitz and glamour of Hollywood, there was a sea change brewing in the barrios of his home town. Inspired by the Black Power movement, the Mexican-American community had begun to organize. This became known as the Chicano Movement.

GR: When the Chicano movement began, I was really interested and I thought I should cover it because I felt I was sort of a part of that movement and I wanted to document it because I didn’t see anybody else doing it.

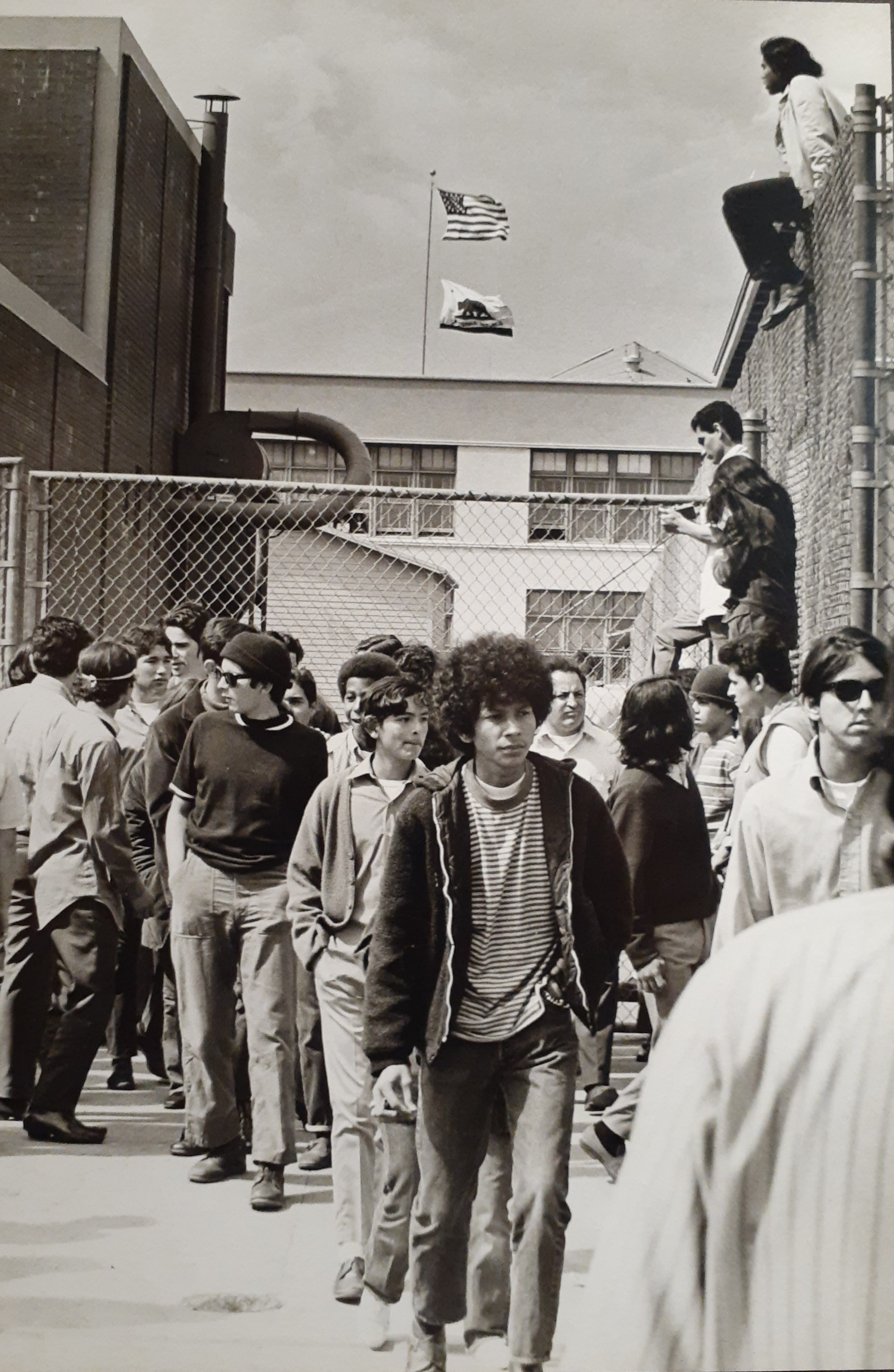

One of the most significant events during the early days of the movement was the school walkout in 1968 organized by high school students protesting the lack of educational opportunities for the Mexican-American community.

GR: I would be working at Columbia and, and there’d be walkouts in East LA at the schools. So I would leave on my lunch hour. I just felt that it should be documented and I could do it. Since I knew something was going to happen, I would just show up there and take pictures.

During the late 60s and early 70s, George continued to document some of the pivotal moments in the Chicano movement.

GR: When it’s happening, you don’t realize how important it is, but you do know that there’s something going on and so you want to document it, but I never realized that how important it would be later on.

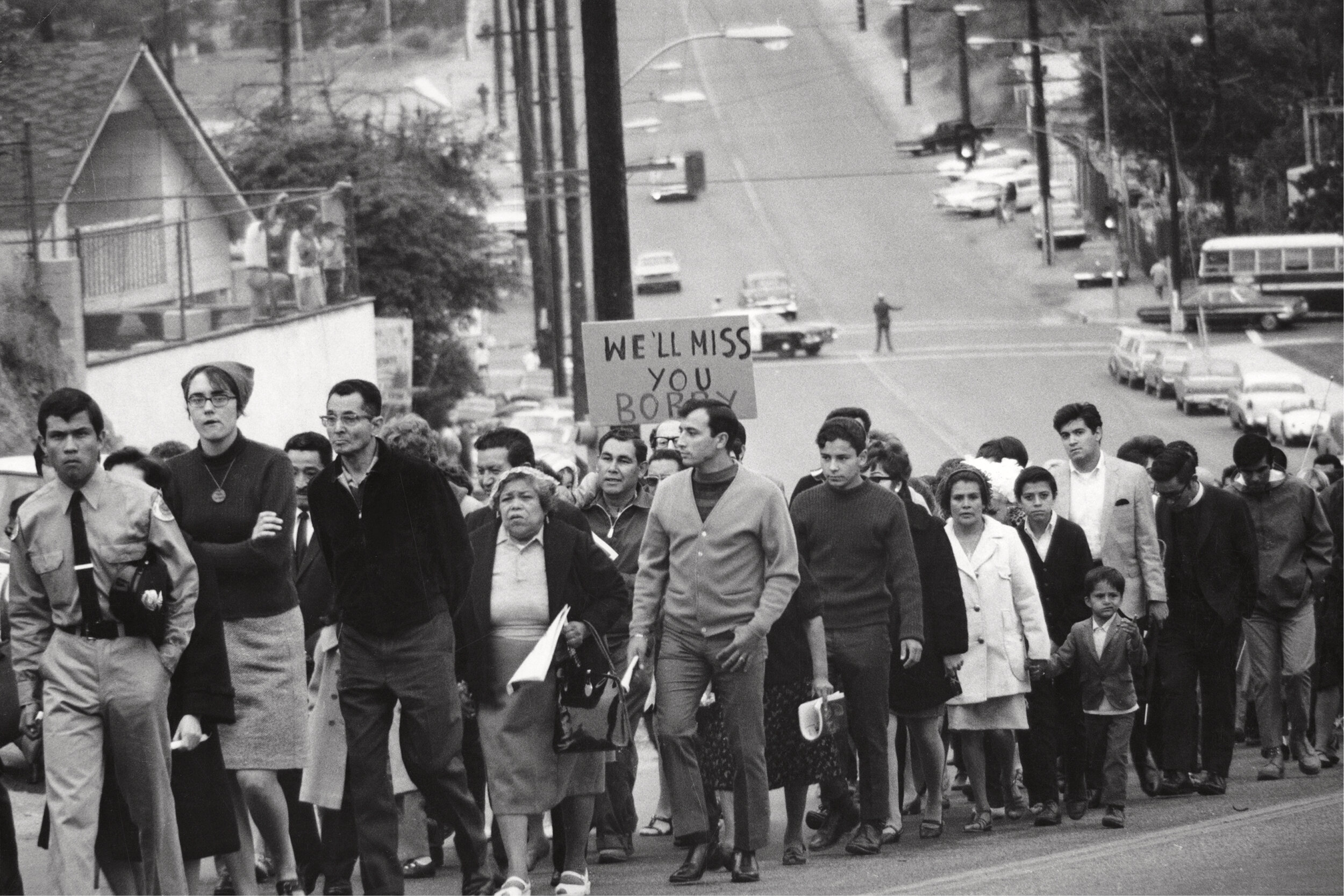

One of his most notable pictures depicted a memorial march in East LA in honor of Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. the day after his assassination.

GR: Robert Kennedy had supported the Chicano rights movement, so his death really hit the community hard.

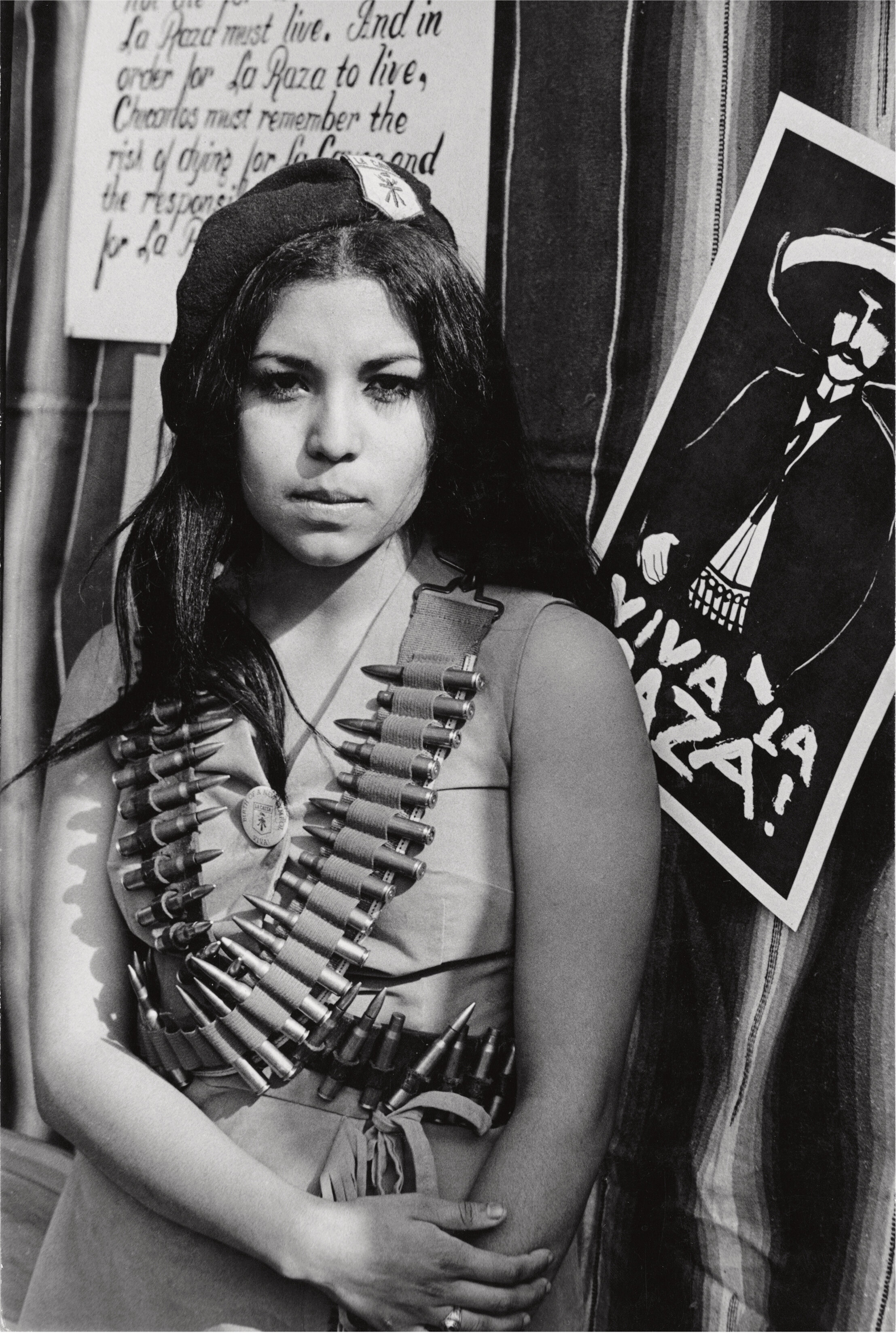

Security for the marchers was provided by The Brown Berets, a Chicano organization that believed in Chicano self determination and self defense of the community against racism and police brutality. Emulating the style of the Black Panthers, they sported brown berets and wore khaki uniforms. One photograph became an striking image for the movement: 16 year-old Chicana activist Hilda Reyes Jensen.

GR: She was a Brown Beret. Later on, that group of women formed their own group called Las Adelitas, because they were dissatisfied that the male members of the Brown Beret movement didn’t take them very seriously.

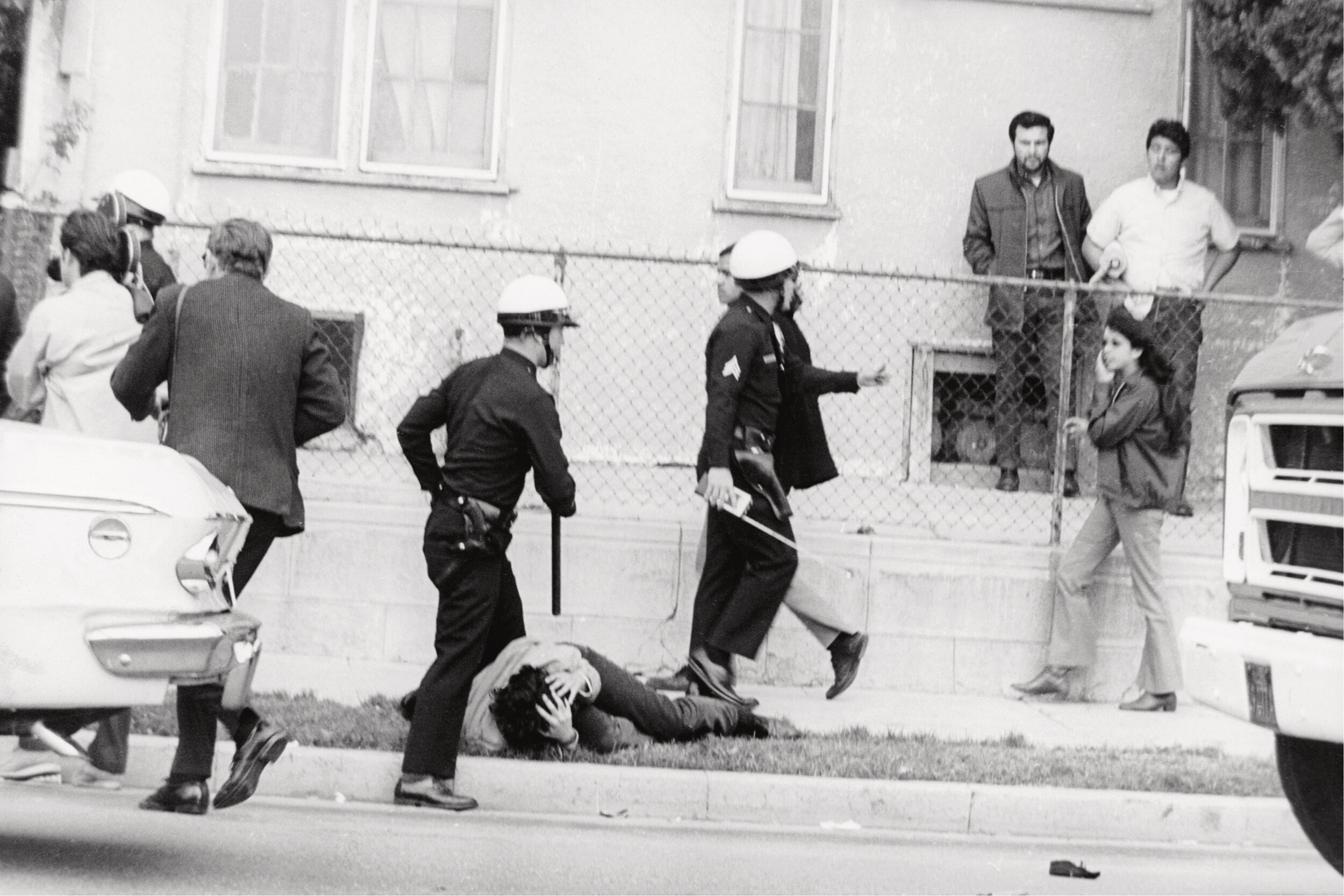

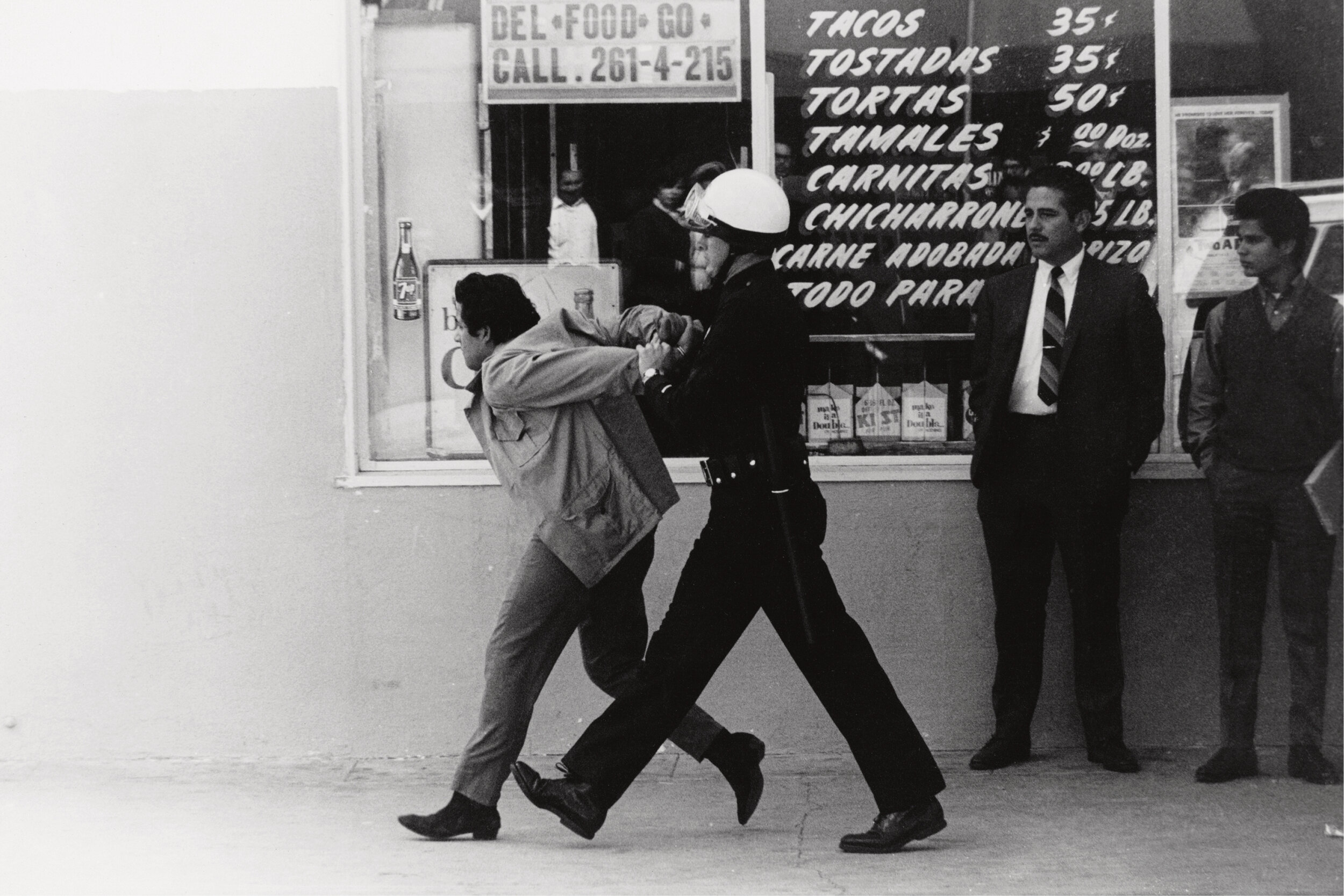

But photographing protests and police actions did not come without risks.

GR: It was kind of risky, you know, cause the cops don’t want you there, and then some older Latino people, they wonder who you are and that has to do with immigration and stuff. I didn’t have like LAPD credentials or anything, so you would get it from both sides and it was like a real challenge.

The turning point for the whole Mexican-American Chicano experience was the Moratorium March in 1970 that was a protest against the Vietnam War because, people felt that there were so many Latinos dying in that war, and that got the attention of everyone because that turned into a riot situation and Ruben Salazar—he was a writer for the LA Times and the director at KMEX— died that day along with three other people. So that got the attention of everyone.

In 1968, George would encounter one of the most influential figures in the Chicano movement—Cesar Chavez, the leader of the United Farm Workers.

GR: People ask you, “Do you recall who your special subjects were?” being a photo journalist and there’s only about three or four, but definitely, Cesar Chavez would be one of them.

I kept hearing the word Cesar Chavez, and you know I had to somehow get out to wherever he was. And then I got an assignment from West magazine that was a supplement with the LA Times. And they sort of put me in a Mexican American bag and so anything related to Chicanos that I would do it for them. So anyway, they assign me to go to Delano to spend some time out there with the United farm workers.

The first moment I met Cesar Chavez, he thought it was surprising that somebody named Rodriguez would be coming from the LA Times, thinking that that time no Latino journalist was working there.

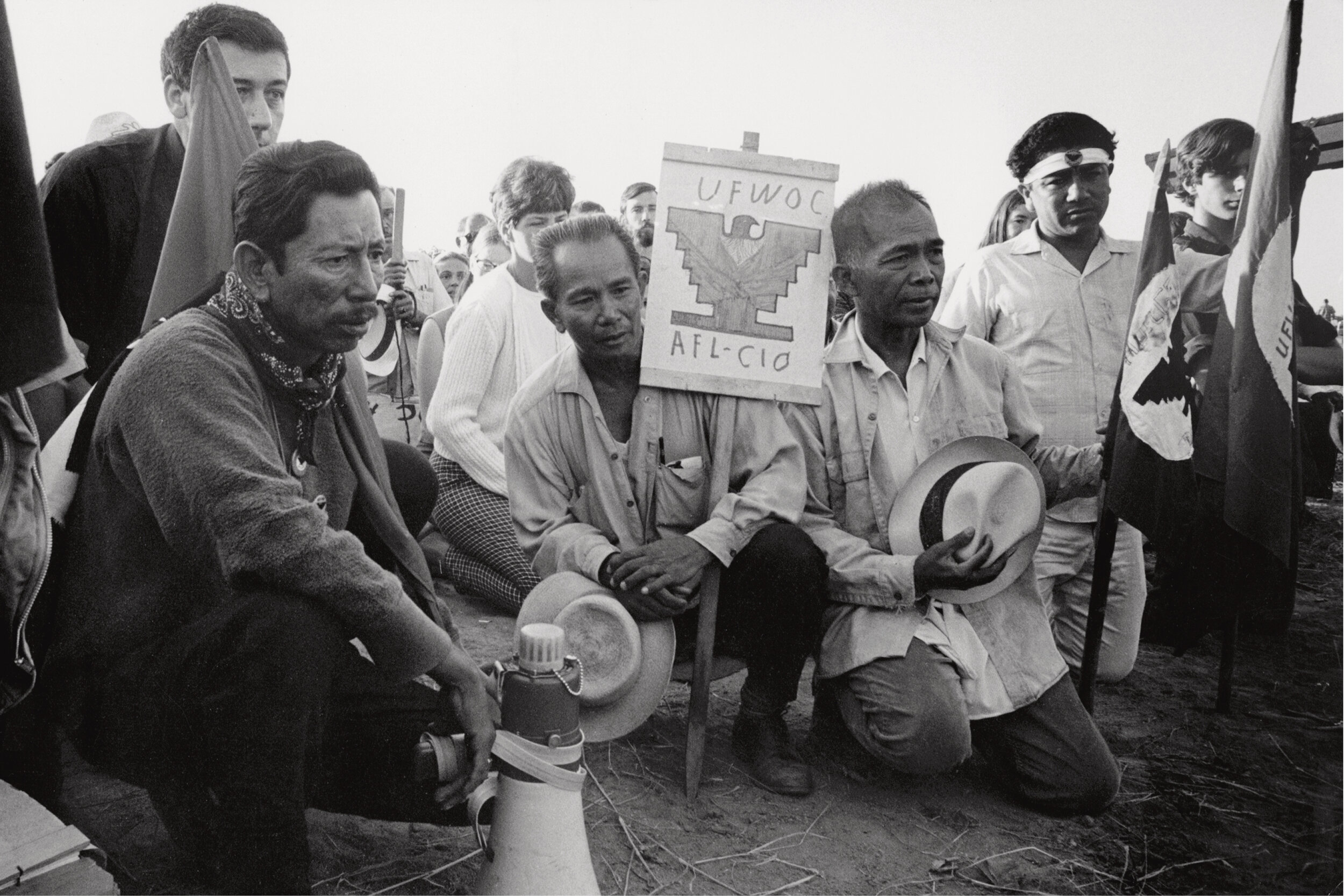

While in Delano, George was struck by the diversity and breadth of the UFW strikers.

GR: There were the great many Latinos, a lot of black people, not too many white people but definitely white people that were out there, demonstrating. It was a mixture of a lot of people that that’s something that’s so special to be there, in the midst of that, because of the people involved.

George is now retired but his body of work is being recognized as a critical artistic and historical resource. His photographs have been featured in numerous museums and galleries, including the Getty Museum, The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles, The Grammy Museum, The Museum of Latin American Art, and The Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Several of his photographs are in the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery collection in Washington D.C.

In 2018, The Double Vision of George Rodriquez, a book-length retrospective of his career, with text by Josh Kun, was published by Hat & Beard Press.

Looking back over his career, George admits he was fortunate that he came of age during a time when photographic journalism was both a profession and a calling.

GR: Photography takes you exactly where you want to be, maybe a movement or something that you will share with us, with people. I tried to document absolutely everything so that people that are not there can get an idea of what was going on, just to document everything so that you can tell a story, and make it as complete as you can.